“You would tell me if I was like that, right?”

My friend and I were sitting in her backyard on one of those uncomfortably hot summer days. The kind where it doesn’t dip below 90 degrees–even in the shade.

We had just finished up a 20-minute character assassination of a person we’d briefly met the night before. A friend of a friend of a friend. And just as we were wrapping up our final thoughts she asked again, “You’d tell me, right?”

Honestly? I thought. Probably not.

The thing is, I wasn’t even sure I knew how to answer that question.

For one, it felt like there was a good chance we likely shared the same character defects, as we had just finished spending the better part of a half-hour needlessly dissecting the personality traits of someone we barely even knew.

If there was something she couldn’t see, would I be able to?

And even if I could–you know, find one thing,–then wouldn’t me telling her only open the door for her to return the favor?

To be honest, I wasn’t sure I was ready for all that. Ignorance is bliss, baby, and I’ll pass.

But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that she might be onto something.

A few months ago, I was listening to a podcast on the subtlety of being rude when I heard the guest mention the Johari Window model.

Named after its creators and American psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham, the Johari Window model was developed to improve communication and trust among members of a group by increasing self-awareness in individuals.

This is how it works:

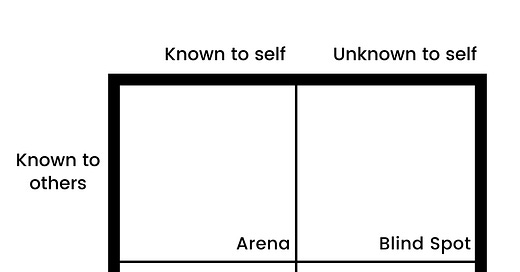

The window is split into four quadrants or panes. Each represents personal information–like feelings, behaviors, attitudes, and traits–that are either known or unknown to oneself or to others.

The arena represents traits that are known to everyone (i.e., to yourself and to others). An example of this would be your communication style. If you detest talking on the phone, and you let others know you feel that way, then it’s no secret, and it would fall in your arena. Now you, and everyone else, know how to (and how not to) communicate with you.

The façade represents the traits that you know about yourself but hide from others. These include past experiences, feelings, fears, or secrets that–if shared–would bring you closer together at the expense of being vulnerable. An example of this would be if you were afraid to swim in the ocean, but instead of telling others, you just made excuses every time they asked you to go to the beach. (So sorry, I have to vacuum my couch on Sunday.)

The unknown is a mystery to both parties, as it represents the traits that neither you nor others know about yourself. These can be feelings, capabilities, or hidden talents that you never even realized you had. An example of an unknown would be finding out that you’re an amazing artist after going to a random drawing class with friends. Some of these traits can remain hidden after experiencing a traumatic event (like maybe your teachers yelled at you every time you doodled all over your notebooks so you swore off drawing forever!) and are mostly discovered by trying something new (and finding that you’ve got a knack) or through observation of others.

And finally, there’s the blind spot. This pane represents the feelings, behaviors, attitudes, and traits that are unknown to you but known to others. This is the sweet spot. The one that we could go our entire lives without realizing. And what a shame when you really think about it. An example of a trait that falls in your blind spot could be that you interrupt people every time you have a conversation, or you name-drop every C-list celebrity you’ve met whenever you get the chance.

What’s hopeful about the model is that it’s anything but permanent. Meaning, that it has the potential to change as often as you do (if you want it to).

Through observation and open communication, you can increase areas that help you grow. And decrease those that hold you back.

For example, if you told your friends that you hate swimming in the ocean, the size of your arena would increase, while your façade would get smaller. Though this would likely change some aspects of your relationship–I don’t think you should expect to receive an invitation to a beach party anytime soon–and simultaneously strengthen your connection because you’re, well, being honest.

Or, instead of disclosing information (maybe you’re a charming oversharer who already tells everyone everything), you could take my friend’s route and simply… ask for feedback.

Although this option can be extremely uncomfortable and painful (depending on how well you take constructive criticism), it has the potential to help you truly see yourself and grow. Tempting, isn’t it?

At this point, I’d like to think that I could take it. From my friends, that is. Those whom I trust the most. Who see me at my best, my worst, and everything in between. Who, for the most part, see me more clearly than I see myself. Who knows, maybe they’ll sit me down and say “Katy, you’re perfectly perfect in every way–don’t ever change a thing!” (A girl can dream, right?)

I’d like to think that now, if given the opportunity, I’d welcome the feedback with open arms and an open mind. (What can I say, I’ve been feeling optimistic lately).

The question is: Would you?

Very interesting & insightful Katy!

I’ve at times felt haunted by attempting to self-decipher my own blind spots - it seems mostly based on the person assessing me as to what they choose to hone in on as a defining, off-putting characteristic of my personality. Yet, sometimes assessing others, I wonder how they don’t clearly see the glaring blind spot in their own personality that seem so obvious to me.

I think Ben Franklin had a pretty good approach to honest self evaluation without involving the natural bias of others that may lead us in the wrong direction. Idk these are just some ramblings on the topic as you got me thinking about it.

Fascinating to analyze, great writing! 👏